|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

Man Pulling a Rope, Bronze, height 10 1/2” Length 27”

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

Slow Dancing, oil on canvas 39 1/2 x 39 1/2

|

||||||||||

|

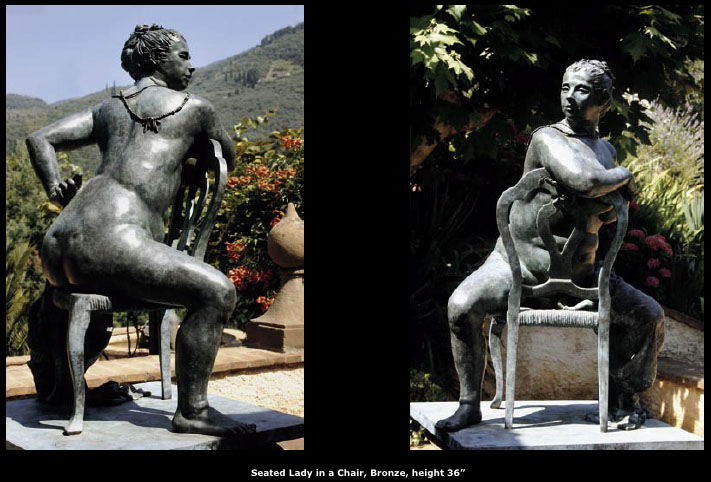

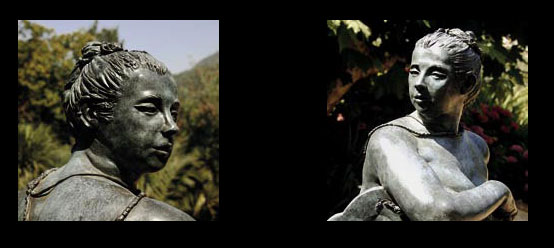

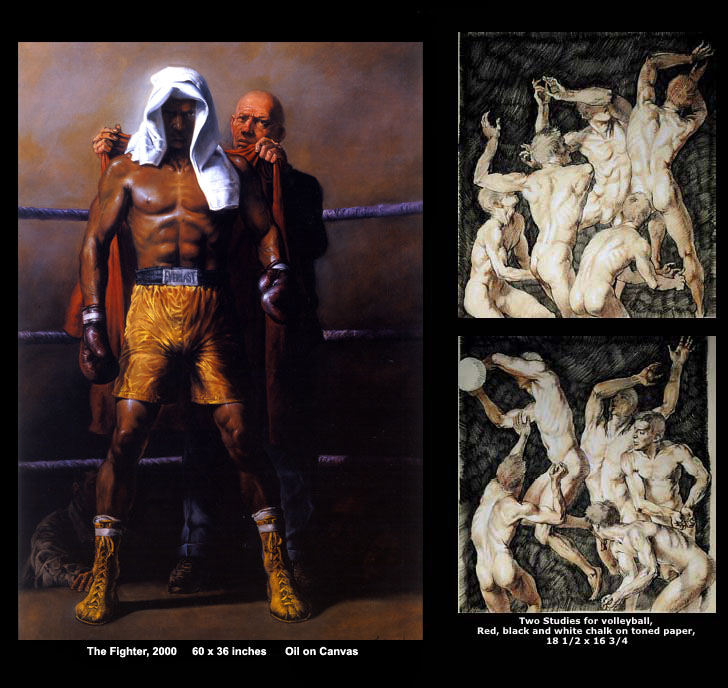

One of the required courses in the first year was Maroger’s still-life painting. Sheppard took the course, but, at that time, he was more interested in Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Jules Pascin than the 17th-century masters that Maroger was heralding. It was not until his third year that Sheppard’s friend and fellow student, Earl Hofmann, encouraged him to come back into the Maroger class. Sheppard had been impressed with the work of Hofmann and other students who had stayed with Maroger from their first year. One week, when Maroger failed to come to Baltimore for his classes, Hofmann prepared a panel and palette with colors and Maroger medium for his friend. Sheppard proceeded to paint his first true Maroger painting. It was an interior with two artists. One artist, an abstract painter, was asleep, and the other, a traditional painter, looked out of the window. The following week, Maroger arrived at the school to find Sheppard in his class finishing his painting. Maroger was delighted and said to him, “Paint three more like that, my boy, and I will get you into a New York gallery.” Maroger was recruiting for his new group, and Sheppard stayed with him until his death. Sheppard became part of the Maroger group and exhibited with them from then on, never to paint abstractly again. An ardent disciple of Maroger, Sheppard enthusiastically embraced the principles of classical art and the use of the human figure in his work. In Maroger’s book, The Secret Formulas and Techniques of the Masters, he writes about drawing, “It is the problem of the draughtsman to represent on a plane his paper the multiple three-dimensional appearances of nature, conveying the impression of light, depth, and movement, as well as the texture of materials, by the sole means of the gradations and modeling in the grays as they go from the white of his paper to the darkest value of his drawing instrument.” Commenting on Michelangelo Buonarroti’s drawings, he writes, “The artist in him was always the dominating force, and he never merely imitated nature. If he exaggerated, it was in order to strengthen the impression he desired to create.” Maroger quotes Paul Valéry, speaking of the old masters, “Not one of them could have believed that his passion for his art would be cooled by a complete mastery of his craft, that strict study and meditation would prevent him from being himself. This is true of only the weak, who do not count in any case.” Maroger believed that Michelangelo and Peter Paul Rubens were the two supreme artists in their field. They were both fantastic draftsmen, but Rubens’s paintings, with their incredible technique and medium, interested him most. The brilliance of the transparent shadows and the opaqueness of the impasto light gave the ultimate in contrast. Only Rubens and Rembrandt van Rijn took this technique to its climax. Maroger had his students copy as many master paintings as they could, much as piano students practice and learn from playing master compositions. To Maroger, the “great art” was finished at the end of the 18th century. With Maroger’s guidance, Sheppard became an excellent draftsman and painter. During the years Sheppard was at the Institute, many established artists came to Baltimore to learn about the Maroger medium directly from Maroger. One such artist was Reginald Marsh, one of America’s great genre painters. Other well-known users of the Maroger medium were the New York painters Frank Mason and John Koch. Marsh had a very strong influence on Sheppard and on all the young Maroger students. Marsh’s social realism led Sheppard to realize the value of combining the human figure within scenes of Baltimore’s urban life, for which he became renowned soon thereafter. Sheppard’s earliest subject matter included life in the black ghettos and the strip joints along Baltimore’s famous Block. In the 1950s, Sheppard painted Blaze Starr, a Baltimore burlesque queen who gained national notoriety. She was featured in Esquire, Life, and other mass-circulation magazines, and her reputation grew still larger, owing to escapades such as a late night, nearly nude romp across the lawn at the estate of Governor Earl Long of Louisiana. Sheppard tells this story about his painting: I did the Blaze Starr painting in 1956, and it was my first major large-scale work. It measured six by four feet. With the hope of promoting my career, my photographer friend Morton Tadder took photos of me painting Blaze’s portrait. Mort said he would be able to get one of the photos placed in a top men’s magazine, either Esquire or Playboy. The following year, I won a Guggenheim Fellowship, which gave me a chance to go to Europe for the first time. Just prior to my departure, one of Tadder’s photographs of me was published not in a relatively classy magazine like Esquire, but in Confidential, a scandal sheet not noted for the accuracy of its reportage. It appeared on the cover, accompanied by the headline, “The Secret Story Behind the Painting.” Inside was a completely concocted tale about Blaze and myself. I fretted that the Guggenheim people would see the magazine and decide to take my prize away. Fortunately, that did not happen. I sold the painting and it changed hands several times, ending up in the Frederick Winner Collection. The photo of me painting Blaze made yet another public appearance a few years ago, this time as an illustration in GQ Magazine for an article about the motion picture Blaze, in which Paul Newman played Earl Long. No credit was given to the artist by GQ. Clyde Singer, assistant director of the Butler Institute of American Art, wrote an essay on Sheppard’s work for his book, The Work of Joseph Sheppard 1957–1980. In it, Singer writes about Sheppard’s boxing paintings, “An important segment of his work consists of the canvases of the prize ring. The mugs are real. Joe has punched a few guys around himself and has been punished in return, so he knows and feels what it’s all about. Likenesses of Floyd Patterson, Mohammed Ali, and others emerge as big as life in his canvases. Sports Illustrated Magazine took note and called upon him to paint a cover of the historic Dempsey-Williard fight for its January 13, 1964 issue.” A footnote to the Sports Illustrated cover was that the feature article claimed that Jack Dempsey’s gloves were loaded with plaster when he won the championship. When Sheppard was introduced to Dempsey at Sheppard’s New York show at the Grand Central Galleries, Sheppard mentioned that he was the one who had painted the cover picture. Dempsey responded that his friend standing beside him was his lawyer and that they were suing Sports Illustrated! Dempsey invited Sheppard to his restaurant afterward and entertained him with magic tricks, and they both had a big laugh about the story and cover. In 1956, Sheppard had become artist-in-residence at Dickinson College in Pennsylvania. The following year he won the John Simon Guggenheim Traveling Fellowship and went to Europe to see the old masters’ works, especially Rubens’s for the first time. Besides copying master paintings in the Louvre Museum, Sheppard started to haunt the clubs and other nightlife in Paris. He drew and painted the derelicts in the Metro entrances; the gypsies, beggars, and prostitutes; and the parks and kiosks. His output in six months culminated in an exhibition that was well received by critics in a gallery in Paris. While in Paris, Sheppard met Camille Versini, who had been a student, along with Maroger, under Anquetin. Versini was trying to promote an oil painting medium of her own, similar to Maroger’s, and had made arrangements with Marc Havel, a chemist for the paint company Lefranc Bougeois, to commercialize it. It was supposed to carry the name “Anquetin,” but when it finally came onto the market it was simply labeled Flemish or Italian medium. Through the encouragement of Maroger, Sheppard sought out the painter Siegfried Hahn, with whom Maroger had been corresponding. Hahn was living in Evreux, France. Sheppard and Versini went together and found Hahn in a one-room rental without heat or plumbing. He had a fever and probably hadn’t eaten for some time. On a table near his bed he had Maroger’s book and a Bunsen burner on which to cook medium. Versini sent Sheppard out for some eggs, and she proceeded to cook Hahn a French omelet over the Bunsen burner, which had a miraculous effect on him and seemed to bring him back to life. After Hahn recuperated, he found a villa for Sheppard near Evreux, in the town of Buei. Hahn became a frequent visitor to the villa and wanted to start a Maroger group in France. In the following months, Hahn arranged lectures throughout Normandy, where Versini would speak about the great oil medium of the 17th century and Sheppard would follow with an hour of portrait demonstration.After Sheppard returned to America, he and other early students of Maroger were making headlines in Baltimore, and the idea of an American school of painting, about which Maroger had dreamed, seemed to be given a new life. In 1961, Sheppard and John Bannon got the idea to take over a recently vacated contemporary gallery and invite their close friends to join them in an exhibition. They called themselves the Six Realists. The six were Sheppard, Bannon, Frank Redelius, Thomas Rowe, Evan Kheen, and Earl Hofmann. The opening night coincided with the opening of the annual regional show at the Baltimore Museum of Art (from which all six had been rejected). Two thousand people attended their opening. The headlines the next day read, “A Triumph in every way.” R. P. Harriss, critic for the News American, wrote a strong review, stating, “Whether this group will form the nucleus of a recognized school dedicated to bucking the nonobjective craze remains to be seen. As of now, they are a credit to their patron, St. Maroger.” Instead of a three-week exhibition of realist paintings by the disciples of Maroger, the gallery remained open and strongly supported for three years. The group of Six Realists changed and included Melvin Miller and David Walsh. Often paintings by the Six Realists were juried into the annual exhibits at the Butler Institute of American Art in Youngstown, Ohio. Most notable was the inclusion of work by Sheppard, Rowe, and Miller in the 1962 Annual at the Butler Institute, along with Ben Shahn and Edward Hopper. Sheppard’s painting, Mr. Mack’s Fighter’s Gym, won first prize in that show. It was a purchase award, and the painting became part of the Butler Institute’s permanent collection. Clyde Singer, then critic for the Youngstown Vindicator, described Sheppard at the time as “one of the most gifted artists in America today.” The Butler Institute has continued to exhibit Sheppard’s work. One such exhibition in 1992, Artists at Ringside, included work by Sheppard, George Bellows, and Thomas Eakins. Eight of Sheppard’s paintings were in that exhibition, including his famous Descent from the Ring. In 2002, Sheppard’s traveling exhibition, 50 Years of Art, was first shown in America at the Butler Institute, after its Italian tour and before it went to Maryland, where it was divided and shown at three locations at the same time: the Walters Art Museum, University of Maryland University College, and Evergreen House. In 1960, Sheppard was asked to teach at the Maryland Institute College of Art, where Maroger had taught a few years earlier. Sheppard taught painting, anatomy, and figure drawing. During the 15 years that he taught at the Maryland Institute, he wrote and illustrated seven books on anatomy, figure drawing, and painting techniques, which have been translated into most major languages. The Maryland Institute’s fine arts department was structured so that all students had to take a fixed set of courses the first year. For the remaining three years, they could select from among a diverse group of teachers with varying techniques and philosophies. Teachers were not obligated to accept more than 20 students into a class. Sheppard never enforced that quota because he was afraid of losing a good student. When a second-year student arrived in his class, he would explain that he was going to teach a special technique. If they wanted to stay in the class, they would have to draw and paint in this technique, the old master way. He demanded punctuality and flawless attendance. By the second week, the class would have dwindled to around the 20-student ceiling.Many students stayed with Sheppard all three years, but some students were little influenced by the class and found their own way. A few, such as Jeff Koons, became world-famous. From his earliest days as an artist, Sheppard had great success in his hometown of Baltimore, in New York, and more recently in Italy, in spite of the fact that the movement of which he was part was not à la mode, as Reginald Marsh had said. Sheppard earned an enviable reputation as a realist painter in various guises and genres, as a painter of street scenes, barrooms, fighters, and strippers. In the last 20 years, living in Italy, Sheppard has turned to sculpture in bronze and marble. Joseph Veach Nobel, chairman of the board of trustees of the Brookgreen Gardens of American Sculpture, wrote:What do you call a person who draws; paints in oil, tempera, and watercolor; sculpts; and writes books on anatomy and drawing and does all of theabove extraordinarily well? Surely a genius. Joseph Sheppard must be the reincarnation of a Renaissance artist. Next, how do you define him? He certainly is an interesting mix of past and present. If you take one part Michelangelo, add an equal amount of [Giovanni Lorenzo] Bernini, stir in a taste of Rubens, and season with dashes of Marsh, [John] Sloan, and Bellows, you have Joseph Sheppard. Besides his many public murals and sculptures, Sheppard turned to portraiture in the 1990s. Among his many sitters are President and Mrs. George Bush; Senator Barbara Mikulski; Mayor and then Governor William Donald Schaefer; Chairman of the Board, Central Petroleum Corporation, Henry A. Rosenberg Jr.; Cardinal William H. Keeler; Archbishop John P. Foley of the Vatican; and opera star Chris Merritt. Recently, Sheppard’s portrait of film director John Waters has been added to the collection of the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Though he left the Maryland Institute 30 years ago, some of Sheppard’s former students still stay in touch. They make up a talented group in their midcareers. These 12 American artists are the fourth generation to continue the legacy, sculptors and painters who are creating, thriving, and teaching. They are Nina Akamu, Nilda Maria Comas, Daniel Graves, Malcolm Harlow, Douglas Hofmann, Michael Molnar, James Earl Reid, Robert Seyffert, Mark Tennant, Larry Dodd Wheeler, Evan Wilson, and David Zuccarini. The Legacy: a tradition lives on. Bibliography Kelly, Cindy. 2002. The early years. In Joseph Sheppard: 50 Years of Art. Firenze, Italy: Arti Grafiche Giorgi & Gambi. Maroger, Jacques. 1948. The Secret Formulas and Techniques of the Masters. New York: Studio Publications.Sheppard, Joseph. Scrapbook and recollections. Singer, Clyde. N.d. The Work of Joseph Sheppard 1957–1980. Florence, Italy: Giorgi & Gambi. Sheppard - “Flowers and Shells”oil on panel, 36x36, 1982Westmoreland Museum or Art, Greensburg Penn.

|

||||||||||