|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

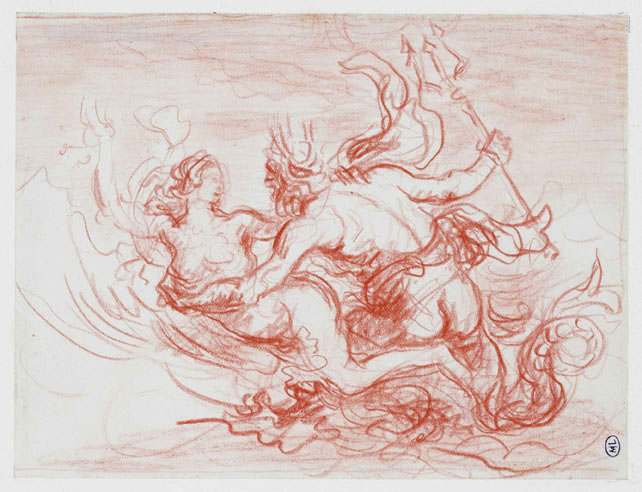

Neptune

|

|||||||

|

REPRODUCTIONS INCLUDED IN EXHIBITION

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

Man, Woman, Soldier

|

|||||||

|

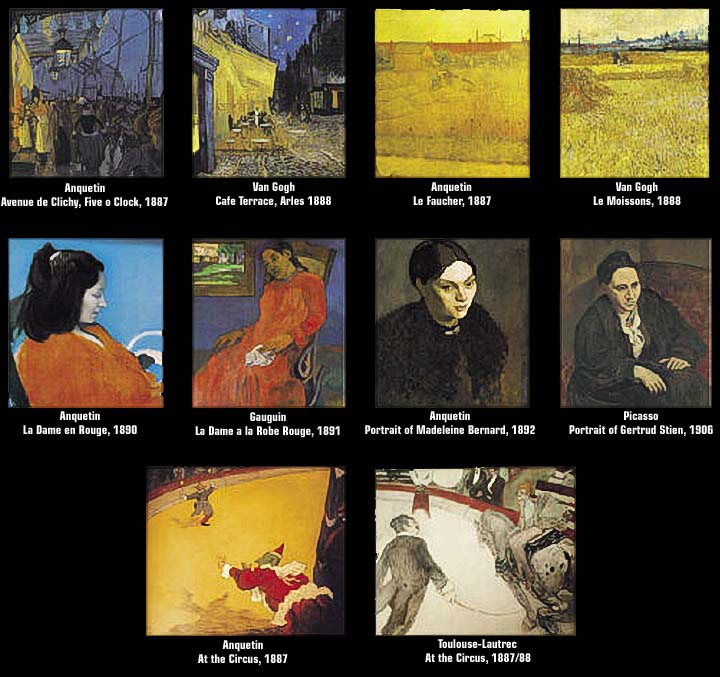

Examples of Anquetin's Influence on his Contemporaries

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

Louis Anquetin was born in Etrepagny, France, in 1861. He moved to Paris in 1882 and entered the studio of Professor Léon Bonnat. There he met fellow student Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and they became good friends. When Bonnat’s school closed, Anquetin and Toulouse-Lautrec moved together to Fernand Cormon’s atelier. Anquetin was considered Cormon’s most promising student and successor. Around 1885, the Cormon group sought to move beyond impressionism and search for a new modern style. The group included Anquetin, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Emile Bernard, as well as Vincent van Gogh. As young students, these artists were in constant need of models, and they often used each other. Some examples of this are an oil sketch (1886) and a drawing (1886) of Toulouse-Lautrec by Anquetin. In 1887, Anquetin did a pastel study of Bernard. Toulouse-Lautrec sketched Anquetin (1886) and did an oil of Bernard (1885), as well as a crayon drawing of Van Gogh (1887). In 1887, Van Gogh presented an exhibition of Japanese prints at the Café du Tambourin and took Anquetin and Bernard to see them. They were both very affected by them. Anquetin, influenced by the Japanese prints, did two pastels and then an oil of L’Avenue de Clichy (1887). These pictures devised an innovative method of painting, using strong black contour outlines and flat areas of color. Anquetin exhibited this oil painting, along with others, at the exhibition of Les XX in Brussels and at the Salon des Indépendents in Paris in 1888. The critic Edouard Dujardin dubbed the new style “cloisonnism” and claimed it as an essential development in neoimpressionism. Anquetin’s young friend Bernard adopted the new technique, and together their work was hailed as the initiation of a new “ism,” much like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque were later hailed as the initiators of cubism. Anquetin’s influence on the Cormon group and other artists can easily be seen. His At the Circus (1887) strongly influenced Toulouse-Lautrec’s At the Circus Fernando (1888), both in composition and style. Van Gogh’s Les Cafe a Arles (1888) is almost a copy of Anquetin’s L’Avenue de Clichy, as is Van Gogh’s Les Moissons (1888) of Anquetin’s Le Faucher (1887). Anquetin influenced other artists in his circle of friends. Paul Gauguin’s La Dame a la Robe Rouge (1891) takes its inspiration from Anquetin’s La Dame en Rouge (1890) and, 13 years later, Picasso used Anquetin’s Madeline (1892) as a model for his portrait Gertrude Stein (1905). In 1894, Anquetin and Toulouse-Lautrec traveled to Holland and Belgium to examine the works of the great northern masters Peter Paul Rubens, Rembrandt van Rijn, and Frans Hals. They acknowledged the differences between the masters’ fluid and brilliant oils and their own, which were opaque and laborious. Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Anquetin also had long discussions about techniques, and they agreed that something was lacking in their materials. Many of the artists had switched to pastel because oil painting was so dull and difficult. So what happened to Louis Anquetin? Why is it we know all of his contemporaries, but only a few connoisseurs know his name? After being one of the chief contributors in the evolution of modern art, Anquetin made an abrupt turn in his career. He abandoned the modern art movement and turned on his colleagues, charging that they, as well as the French academicians, lacked the understanding of oil painting that was their heritage. He believed the essential difference between his contemporaries and the old masters was not talent, but the lost knowledge of an incredible oil painting technique and the ability to draw based on the study of anatomy. His only friend from those early years remained Toulouse-Lautrec, probably because of their mutual respect for each other’s draftsmanship skills. Anquetin entered the laboratory of dissection at Clamart in 1894 and studied with Professor Arroux for two years. Anquetin felt that the knowledge of anatomy possessed by artists like Michelangelo Buonarroti and Rubens gave them freedom to create figures without being slaves to the model. During this time, Anquetin made many experiments, trying to find the old masters’ methods and materials. Because his research and his subject matter changed from the contemporary scene to the antique, his reputation quickly disappeared. After the mid-1890s, he was no longer making news. Anquetin may have been the pioneer who actually began to test and experiment to rediscover the lost secrets. In his La Peinture de Rubens, he says about himself and his colleagues, “Poor beggars that we are, no matter how much talent we have, nor how hard we strive, we are fore-doomed because the best means of expressing ourselves in oil paint is a lost knowledge and inaccessible to us.” He was aware of some differences of procedure. He commented in his book that the old masters’ palettes were small and set with a few, almost nondescript-looking colors, out of which they made jewels on their canvases. The contemporary artists’ palettes were enormous by comparison and set with a dazzling array of colors, and they produced drab paintings. Anquetin stressed the urgent need to regain an understanding of the means by whichRubens obtained his technical knowledge and expression, for in his paintings, above all of the others, is found the best qualities combined. To understand how Rubens achieved his results is to realize how all of the other masters obtained theirs. The sheer efficiency of Rubens’s paintings gives the widest range of effects from the simplest basic means. Anquetin’s theory was that the old master paintings had an underpainting in black and white, and the colors were glazed on. In some cases this could be so, but documents stating that some of Rubens’s heads were done a la prima (in one sitting) in a couple of hours presented a baffling problem. Anquetin struggled with failure after failure in his quest, until his former pupil, assistant, and friend, Jacques Maroger, made a discovery. Bibliography Brame and Lorenceau Gallery. 1991. |

|||||||